A Reflection on the Experience of Taking Charge of the Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures’ Exhibitions for Fiscal Year 2011

★

Summary

The “Coordinated Exhibitions of Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai” were jointly held in 2011 by nine museums from Kansai that hold acquisitions of such works. Having taken charge of the exhibitions at the Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures, one of the participating museums, the author reminisces about the coordinated exhibitions, reappraises the significance of the acquisitions of Chinese artistic works in the Kansai area, and delineates prospects for future research on these acquisitions.

The Main Text

The Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures is a research institute and art museum in Nishinomiya City, Hyogo Prefecture. Registered as a public interest incorporated foundation, its main objectives are to maintain and take care of a set of ancient cultural assets of China and Japan that were originally collected by three generations of the Kurokawa family, which used to run a securities dealing business in Osaka. The Institute holds a month-long public exhibition twice a year, in the spring and in the autumn. For over a year centering in 2011, the “Coordinated Exhibitions of Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai” was a joint project planned and engaged in by nine museums in the Kansai area. The Kurokawa Institute took part in this joint project, holding two exhibitions, one in the spring and the other in the autumn. The Institute regularly exhibits painting and works of calligraphy in its possession, but it rarely holds exhibitions, which, like the two it held in 2011, focus exclusively on Chinese paintings and calligraphy. The two exhibitions in 2011 were the first in more than 20 years since the “Paintings of China” exhibition of 1988 and the “Calligraphic Works of China” exhibition of 1991.

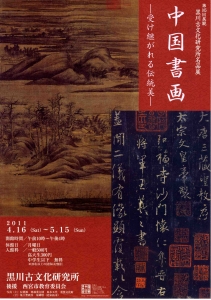

The Spring Exhibition: “Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works: Traditional Beauty Handed down from Ancient Times”

Under the title “Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works: Traditional Beauty Handed down from Ancient Times,” the Spring Exhibition, which ran from April 16 to May 15, displayed works in the possession of the Institute, as well as some of the excellent pieces constituting the Yamaoka Collection, which was deposited with the Institute several years ago. The works of Chinese painting and calligraphy in the Institute’s possession were collected by Kurokawa Kôshichi (1871-1938), the second head of the Kurokawa Kôshichi Firm, in the Taisho era and the early years of the Showa period from the early 1910s to around 1930. Because China was at that time in the state of turmoil caused by the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy were hemorrhaging abroad in enormous volumes. Naito Konan (1866-1934), a sinologist and a member of the Kyoto School, took a serious view of this situation and urged influential leaders of the business and political worlds in the Kansai area to start to systematically acquire these Chinese works so as to prevent them from being scattered and lost. Included among a number of acquisitions that were launched in response to Naito’s call were the collection of Ueno Riichi (1848-1919), former president of the Asahi Shimbun Company (which was later donated to the Kyoto National Museum), the collection of Abe Fusajiro (1868-1937), former president of Toyobo Co. Ltd., (which was later donated to the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts), the collection of Fujii Zensuke (1873-1943), politician and businessman, who established the Fujii Yurinkan Museum (in which the collection is now housed), and the collection of Kurokawa Koshichi.

<Flyer advertising the Spring Exhibition: “Chinese Paintings and |

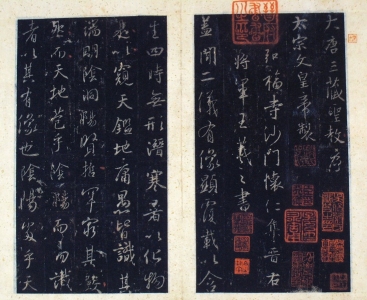

The most salient feature of the history of Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy is that such works have grown dazzlingly rich and consummate, because generations of artists, while basically abiding by the tradition of the classics, have also continuously endeavored to add new elements of creativity to that tradition. Keeping this in mind, the Spring Exhibition planned to emphasize the power of such a lineage. With regard to works of calligraphy, works by or related to Wang Xizhi – such as “Ji Wang Sheng Jiao Xu” Bei Song ta ben (a Northern Song rubbing of the “Preface to the Great Teachings”), and “Lan Ting Xu Xiao Juan” (a small scroll “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion”) by Wang Shu and others in the Qing Dynasty period – were exhibited first. These were followed by Early Qing works from the Calligraphic School of “Tie Xue” (Imitating Copybooks), including Shen Quan’s “Lin Huai Su Zi Xu Tie” (Hand Copy of Huai Su’s Calligraphy), and Cheng Qin Wang’s “Lin Wang Xizhi Tie” (Calligraphy in the Style of Wang Xizhi). By contrast, the paintings began with “Han Lin Zhong Ting Tu” (Wintry Groves and Layered Banks) attributed to Dong Yuan, the founder of the Nanzhonghua School (Southern School of Chinese Painting), who was active during the Five Dynasties period. This was followed mainly by Nanzhonghua School, but included “Fang Dong Yuan Shanshui Tu” (Landscape after Dong Yuan) by Jiang Ai from the Late Ming Dynasty and “Fang Li Cheng Shanshui Tu” (Landscape after Li Cheng) by Shang Rui, who was active during the Qing Dynasty. After displaying a total of 52 pieces, I realized once again that the acquisitions of Kurokawa Koshichi Jr. were strongly influenced by Naito Konan’s views on calligraphy and painting, which attached importance to the Tie Xue Calligraphic School and the Nanzhonghua School. Thanks to this fact, we were able to display a large number of works of calligraphy that were executed by means of “Lin Shu” (i.e. writing by observing and imitating the works of Wang Xishi and other old masters of calligraphy) as well as a large number of paintings drawn by means of “Fang Gu” (i.e. drawing by modeling after the style of the paintings of Dong Yuan and other great painters of the Song and Yuan Dynasties). Many of the works displayed remain in the same state of mounting as they were at the time of acquisition, and the superbly elegant craftsmanship of the mounting was mostly done by using the basic tones of white and watery blue colors that suited the taste of the literary artists of the Qing Dynasty period. As such, the forms in which the displayed works were mounted also gave a special feel to the atmosphere of the exhibition rooms.

<“Ji Wang Shen Jiao Xu” Bei Song ta ben (Northern Song rubbing of “Ji Wang Shen Jiao Xu”)> |

<“Han Lin Zhong Ting Tu” (Wintry Groves and Layered Banks) attributed to Dong Yuan > |

Let me now turn to the works of the Yamaoka Collection that were displayed as part of the Kurokawa Institute’s Spring Exhibition in 2011. Mr. Yamaoka established his collection while receiving tutelage from Mr. Hashimoto Sueyoshi (1902-91), who built up the Hashimoto Collection in Takatsuki City, Osaka. This latter collection is now deposited with the Shôtô Museum of Art, operated by Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward. Given this background, the Yamaoka Collection shares much in common with the Hashimoto Collection in putting emphasis on the works of paintings by artists belonging to various schools of painters in cities south of the Yangtze River from the late Ming Dynasty to the early Qing Dynasty. To our great delight, we were able to display works of artists belonging to the Jin Ling School, which are included in the Yamaoka Collection but are not well represented in the Kurokawa Collection, namely Chen Zhuo’s “Shanshui Tu” (Landscape Painting) and Wu Dan’s “Shanshui Tu” (Landscape Painting). It is also noteworthy that we were able to display “He Bi Shanshui Tujuan” (Landscape Reunited) by Gu Dashen and Zhu Xuan from the Qing Dynasty period – the work mentioned in the pre-war catalogue of acquisitions in Kansai titled Kôhansha Shina Meigasen (Kôhansha’s Selected Great Pictures of China, published by Bunkadô Shoten, 1927) – along with Gu Dashen’s “Xishan Shixing Tujuan” (Poetically Inspiring Gorge and Mountains), which is in the possession of the Institute. By bringing together works included in both the old and new collections in the Kansai area and by displaying them side by side, this exhibition also seems to have highlighted the importance of passing these collections down to future generations.

<An exhibition room of the Exhibition “Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works: Traditional Beauty Being Handed down from Ancient Times”> |

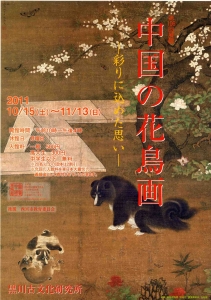

Autumn Exhibition: “Flower-and-Bird Paintings of China: The Feeling Put into Their Coloring”

The Autumn Exhibition, which ran from October 15 to November 13, 2011 under the title “Flower-and-Bird Paintings of China: The Feeling Put into Their Coloring,” homed in on the flower-and-bird paintings of China, paying attention to how the genre changed over time and the meanings of its motifs. We planned the layout of the displays in such a way as to enable viewers to roughly trace the genealogical development of the works by seeing the exhibits in one room. This trajectory began with the designs and patterns of flowers and birds inscribed on precious stones and pieces of bronze ware of the Yin and Zhou periods, on Warring States Period and Hang Dynasty mirrors, on pieces of gold and silver ware from the Tung Dynasty, and it included the flower-and-bird paintings in the Academy Style from the Song and Ming Dynasties. It ended with the flower-and-plant paintings by literary artists during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. We were able to display these works, which were produced over a period of roughly 3,000 years, from craft works of the ancient times to Yangzhou Baguai (the eight eccentrics of Yangzhou) from the Qing Dynasty. This was made possible by the fact that Kurokawa Koshichi Jr., guided by his strong academic interest, eagerly collected articles on a very extensive scale, including in his collection many background and reference materials.

<Flyer advertising the Exhibition of Chinese Flower-and-Bird Paintings> |

It should be added, however, that, insofar as the paintings are concerned, the Kurokawa Collection, with its focus on nonzonghua (works of the Southern School of painting) in the Ming-Qing period, does not include many Song and Yuan paintings or works of the Zhe school, which were imported in the early days. The only exception is Ji Zhen’s “Chun Yuan You Gou Tu” (Dogs Playing in a Garden in the Spring), a masterpiece of the Ming Dynasty Court Painting Academy. This work was added to Kurokawa Koshichi Jr.’s collection in his last years when he purchased it from Mr. Harada Gorô of Hakubundô Publishing. We were able to make up for this weak spot in the Kurokawa Collection by borrowing 11 works for display in the Autumn Exhibition from the Kyoto National Museum, the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, and from private collectors in the Kansai area. Consequently, we were able to display various paintings, including the flower-and-bird paintings of the Zhe School in the Ming Dynasty, paintings of flowers by literary artists and flower-and-bird paintings of the Shen Nanpin School from the Ming-Qing period. We were also able to display them in such a way as to highlight where the works of professional artists differed from those of the literary artists, as well as how the style of painting changed over time from the age of Lu Ji to that of Shen Nanpin. As for the works of the Nanpin School in the mid-to-late Tokugawa period, Mr. Sugimoto Yoshihisa, my fellow researcher at the Institute, took charge of their display. We were able to borrow a total of six works that had remained virtually unknown, including Iwai Kôun’s “Sôkakuzu” (A Pair of Cranes), and Kakushû’s “Ganjô Hakuyôzu” (A White Hawk on a Lofty Rock). Given the fact that these works were borrowed under such strict conditions that we could not spend more than one day to transport all of them and therefore had to gather them all from within a limited area, we realized once again that the Kansai area is very rich in terms of its acquisitions of works of fine art.

< Ji Zhen’s “Chun Yuan You Gou Tu” (Dogs Playing in a Garden in the Spring)> |

On November 12, when the “Coordinated Exhibitions of Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai” were being held, the Kurokawa Institute co-hosted with the Kwansei Gakuin University Museum Planning Office an “Open Workshop on the Study of Cultural Assets through the Examination of Originals and Their Digital Images: Closing in on the Coloring of Chinese Flower-and-Bird Paintings.” The workshop focused exclusively on high definition digital images of Ji Zhen’s “Chun Yuan You Gou Tu” (Dogs Playing in a Garden in the Spring) shot by Mr. Fukai Jun of the Kwansei Gakuin University Museum Planning Office. A panel consisting of Mr. Nishio Ayumu (of Ritsumeikan University), Mr. Tsukamoto Maromitsu (of the Tokyo National Museum), and Mr. Takenami Haruka (of the Kurokawa Institute), and moderated by Mr. Sugimoto (of the Kurokawa Institute), held a two-hour discussion on various features of this work, as revealed by the digital images, such as the techniques used, its state of preservation and repair, its modality, and the period when it was created. With each member of the panel freely expressing his views on various features of this specific work, and, in keeping with the progress of the discussion, panel discussions of this particular style proved far more effective in encouraging lively exchanges of opinion than prepared lectures and presentations of academic papers. Given their great potential for enlivening research and exhibition activities, I would like to continue to plan and organize similar panel discussions in the future.

<An exhibition room of the Autumn Exhibition: “Flower-and-Bird Paintings of China”> |

Prospects for the Future: Activities of the Study Group on Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai

Kansai has a long tradition of acquiring Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy. Especially in the early modern period, a large number of collections were built up. However, with the passage of approximately one century since such acquisitions were made, memories of those days are becoming increasingly blurred and obscure. The “Coordinated Exhibitions of Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai” were the brainchild of the “Study Group on Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai” and they were organized by curators in charge of Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy at the museums in the Kansai area that possess these works. Established for the purpose of promoting research and public awareness concerning Chinese fine arts, the group had been undertaking joint research by holding a digital image recording session once a month since 2010, recording not only images of the fine details of the works themselves, but also textual data, including tiba or daibatsu (words written at the end of a calligraphic work or a painting) and hakogaki (an autograph or note of authentication written on the box containing an art work). As the group made headway in its research, it began to produce findings revealing that the collectors of Chinese arts in Kansai differed significantly from each other, in terms of both their personal characteristics and the current of the times under which the works were acquired. The Kurokawa Collection was less systematic than other well-known collections, such as the Ueno, Abe, and Fujii Collections mentioned earlier, in acquiring the works of various schools of artists from different periods. Also, the number of works by great masters included in this collection is by no means large. Nevertheless, a most salient feature of the collection is that its acquisitions are not limited to works of painting and calligraphy, they also contain an enormous number of aesthetic and archeological materials from both China and Japan, such as pieces of bronze ware, mirrors, antique coins, and Japanese swords. This feature seems to be a manifestation of the deep interest Koshichi had in cultural heritage. (For biographies and the acquisitions of Koshichi and other collectors, please refer to Sofukawa Hiroshi, editor-in-chief; Kansai Chugoku Shoga Korekushon Kenkyukai (Study Group on Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai), ed. Chûgoku Shoga Tanbô: Kansai no Shûzôka to Sono Meihin (An Inquiry into Chinese Calligraphy and Paintings: Masterpieces Acquired by Collectors in Kansai), Tokyo: Nigensha, 2011.) A curator can learn a lot by comparing the works in the possession of his/her own museum with those owned by other museums. We are determined to continue to make efforts to plan and organize exhibitions that are both academically meaningful and attractive, not only by exploiting the particular traits of the acquisitions in the possession of their own museums but also by displaying works deposited by private collectors, purchasing new works, and borrowing works from other museums or private collectors.

The number of researchers in Japan who specialize in Chinese works of calligraphy and painting is on the decline. On the other hand, there are cases where college graduates after landing jobs in museums without receiving professional training in the area are assigned to take charge of Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy. Given this situation surrounding Chinese fine arts, it seems possible for museums possessing these works to collaborate with each other and make joint efforts to train and educate new generations of curators-researchers. Furthermore, because of ongoing economic trends, an increasing number of Chinese paintings and calligraphic works are reported to be hemorrhaging out of Japan. In order to stem such an outflow, and to increase the number of collectors and lovers of these works, it seems indispensable to look into and reaffirm the significance and the main characteristics of each collection and treat its acquisitions as invaluable cultural assets of the museum’s home area, as well as of the country as a whole. I for one am determined to do what little I can to help the Kansai area make its fair share of contributions to the advancement of studies on Chinese paintings and works of calligraphy.

References

Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures:

http://www.kurokawa-institute.or.jp/

“Coordinated Exhibitions of Collections of Chinese Paintings and Calligraphic Works in Kansai”:

http://www.kansai-chinese-art.net/

★

TAKENAMI Haruka

Researcher, Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures