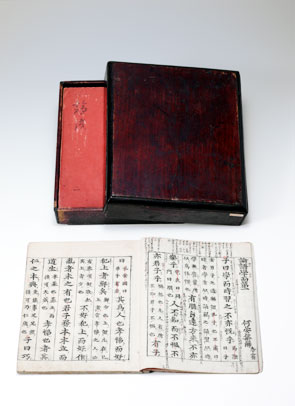

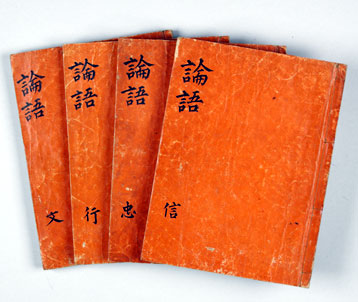

Recently the Institute of Oriental Culture received a donation of eleven rare Chinese literary works from the collection of Zenjiro Yasuda, including a number of Shohei era (1346-1370) editions of the Analects of Confucius. I would like in this short report to introduce the eleven items briefly and explain their significance.

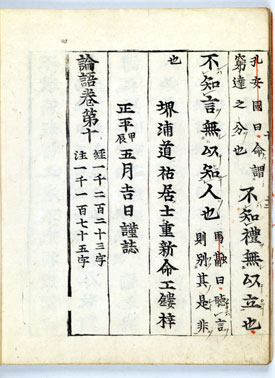

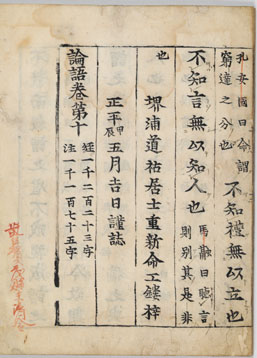

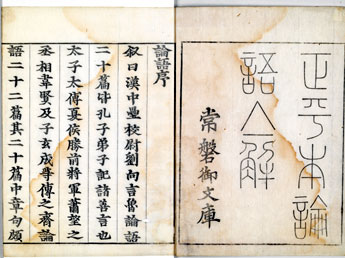

1. Analects, Shohei era edition with one colophon, earlier printed version

Listed by Kazuma Kawase on p. 1664 of his Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu (A Study of Japanese Bibliography, Dainihon yubenkai kodansha, 1945). This edition is in a good state of preservation, rare among the other extant Shohei-era editions. It bears the impression of a red seal of ownership saying “Yonezawa collection,” which tells us it once belonged to Naoe Kanetsugu (1560-1620). The fact that it used to belong to a famous daimyo house adds to its value. At the end of the first volume is an inscription (shikigo) dated 1877 (given in terms of the Chinese era name) saying it belonged to Zhang Zifang. Zhang has been identified as a lecturer in Chinese in the early years of the Tokyo Imperial University.

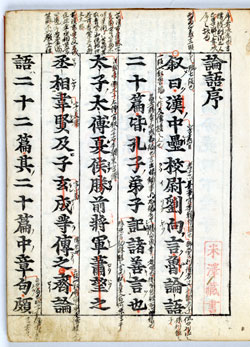

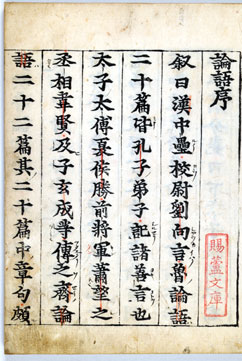

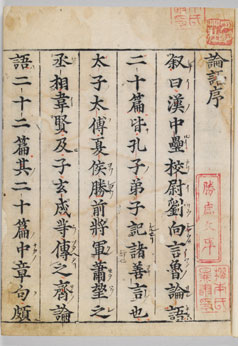

2. Analects, Shohei era edition with one colophon later printed version

Listed by Kazuma Kawase on p. 1669 of his Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu. At the end of each volume there is a red seal impression bearing the name “Sanni Kamo Kenshu Seirei.” We have no means of knowing who this person was. There is another seal of ownership inscribed with the words “Shiro bunko;” this was the name of the library belonging to Shinmi Iga no kami Masamichi (1791-1848), a Tokugawa retainer (hatamoto) and magistrate of Osaka. The name of this work appears in the catalogue of this library.

3. Analects, Shohei era edition with double colophon (not volumes nine and ten)

Listed by Kazuma Kawase on pp. 1630 and 1688 of his Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu. Bears the ownership seal of the Katsushika bunko (library).

4. Analects, Meio era edition

Listed by Kazuma Kawase on p. 1689 of his Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu. A facsimile edition of the double colophon edition, printed by Sugi Takemichi, a retainer of the Ouchi house of Suo (Yamaguchi), in Meio 8 (1499). The Shohei era edition had been printed in Sakai, south of Osaka, an Ouchi holding. The Suo edition may be considered a reprint. A marginal note contains phrases such as “these two characters do not appear in the house edition.” “House edition” refers to the text of the Confucian scholar Kiyohara Nobukata (1475-1550).

5. Analects, Shohei era facsimile edition (fukkokubon) by Ichino Meian (1765-1826) with one colophon

Printed 1813. Has a preface by the bibliographer, editor and bookseller Kariya Ekisai (1775-1835).

6. Analects, Shohei era facsimile edition (fukkokubon) by Ichino Meian (1765-1826) with one colophon

Inscribed “Tokiwa Gobunko.” Does not contain the Kariya preface.

7. Analects, Yohoji edition

Blockprinted.

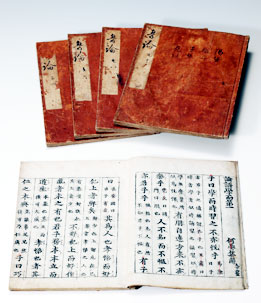

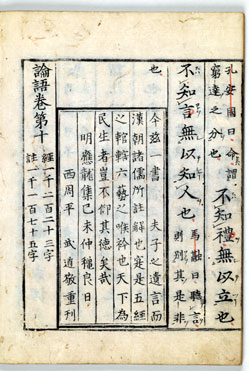

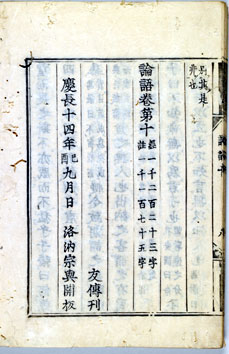

8. Analects, Keicho era (1596-1615) edition, movable type.

Recorded in the journal Shoshigaku (Bibliography) 3:1 (1934) as being listed in the Catalogue of Kokatsujiban (old movable-type editions) in the Yasuda Library, Vol. 9 (p. 57). This is considered the best of all the kokatsijiban. It bars the ownership seal “Gohon” and was part of the collection of the Tokugawa lords of Kii (Wakayama).

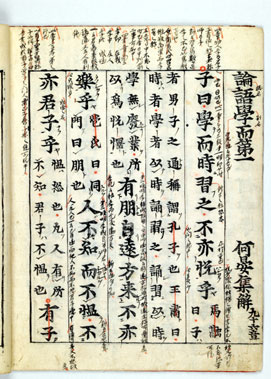

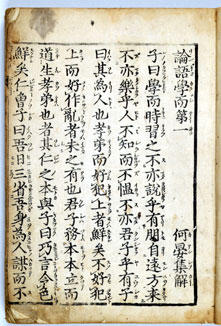

9. Analects with kana commentary

Edo period edition. A commentary in Japanese and written in kana is included next to the main text written in characters.

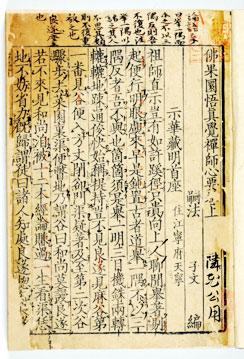

10. Foguo Yuanwu Zhenjue Chanshi Xinyao

Printed book, Southern Song China. A number of “supplementary” pages (hosha, those added later from other blocks). There is also a Gozan edition of this book, but Southern Song version has supplementary pages at the end of the first and last volumes concerning other printed versions. It is thus important for the study of printed books.

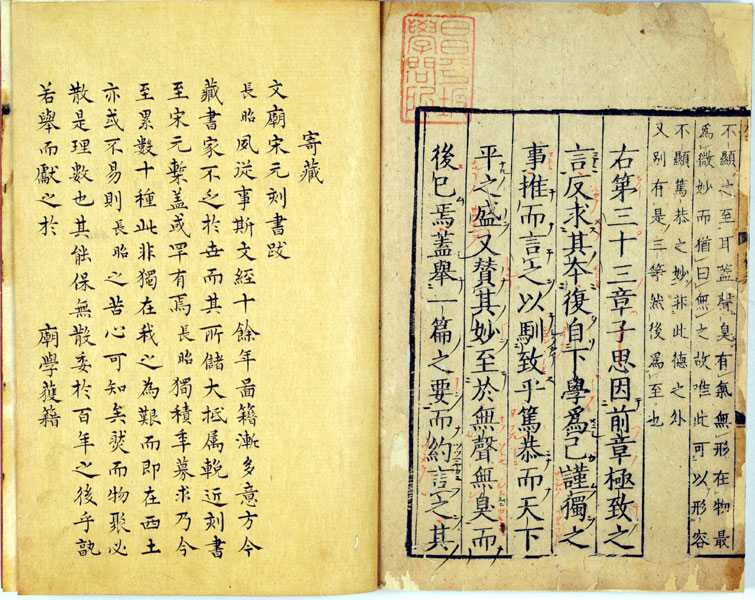

11. Yilijing zhuan tongjie, Vol. 17

Printed book, Southern Song China. The Institute of Oriental Culture owns a complete Song edition of this work. However it is not the same printing as the line arrangement is different. It is one of the thirty Song and Yuan books that the daimyo Ichihashi Nagaaki donated to the Confucian temple in Edo during the Edo period. It bears the ownership seal of the Shoheizaka Gakumonjo, the Bakufu Academy, of which the temple was a part, and so has a distinguished history. The other twenty-nine books are in the Naikaku Bunko (Cabinet Library, now part of the National Archives of Japan) and other libraries.

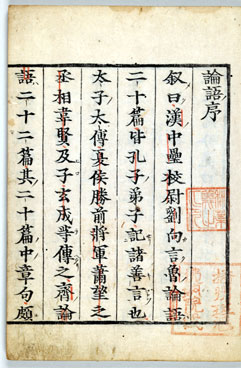

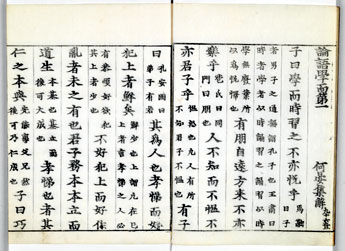

Let us now examine the books more closely, starting with the six examples of the Shohei edition of the Analects. The Shohei edition is regarded as being very important as it preserves the oldest printed form of the Analects. Qing collectors also prized it as the “Korean” edition. A reprint using blocks written and carved in Japan (honkokubon) was published in the Guyi congshu (Collection of lost ancient works, 1882-1884), Chinese texts collected in Japan by the Chinese Minister Li Shuchang (1837-1898) and Yang Shoujing (1839-1915). This edition of the Analects was also selected for publication in the series of photographic reproductions of classical Chinese works called the Sibu congkan (Collected publications from the four categories, Commercial Press, Shanghai, ca 1920-1930), which has been the most influential work of its kind in modern times. Thus the Shohei edition of the Analects has been highly regarded not only in Japan but in China as well as the most important of the printed editions of that work. It is important in Japan too in terms of intellectual history and the cultural history of printing as the earliest of the Confucian classics to be printed. Moreover, it is the most famous of the old printed Japanese books and it is by far the greatest in value.

However, there were many printings made and their connections were later little understood. Further, a great many editions of the Analects were published in the Edo period and later. In the modern period, research became much easier as comparative studies of old printed books began to be undertaken in a number of libraries and archives around the country, and the study of the Shohei edition also made great progress. Finally it was Kazuma Kawase who solved the problem of the how the numerous versions of the Shohei edition related to one another.

There are three basic types of the Shohei edition of the Analects: one with two colophons, those with one colophon, and those with none. It was early realised that the version with no colophon had been made from the same woodblock as that with one colophon; the colophon had simply been erased. The problem was the chronological relationship between the version with two colophons and that with just one, for they were completely different both in terms of size and character shape. Which was made first? Which was the honkokubon reprint? The single-colophon version contains in places revisions of some characters in the double-colophon version, while the double-colophon version has simple errors in character shape not found in the single-colophon version. In the face of such contradictions, it was not easy to determine which came first. Kawase studied the extant versions of the Shohei edition to the greatest extent possible and discovered the existence of another type of the double-colophon version, different from is generally called by that name. This new discovery he showed to be the real Shohei edition, while the other double-colophon versions were, like the single-colophon versions, no more than honkokubon. This hypothesis has been accepted as the established theory down to the present, and is unlikely to be revised unless some hitherto unknown version is found.

The real Shohei edition that Kawase discovered is in the collection of the Osaka City Library. He also verified that this library possesses part of the same version that is held by the Imperial Household Agency. And it was Zenjiro Yasuda who greatly supported this research of Kawase’s when he was a young scholar, both in terms of general assistance and by giving him free access to the valuable works he had collected in his own library. Kawase himself expressed his deep gratitude to Yasuda as his benefactor in what was one of his most important works, the afore-mentioned Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu.

Kawase initially collected together his research into the Shohei edition of the Analects in an article called “Shoheibon Rongo ko” published in the journal Shibun (13:9, 1931). This was later revised and included in Nihon shoshigaku no kenkyu. The works studied in this chapter include the six versions of the Analects (those of the Shohei edition, as well the later honkokubon editions) that were in the Yasuda Collection and which were among the items donated to the Institute of Oriental Culture by Hiroshi Yasuda. These precious works and the support of Zenjiro Yasuda were what enabled Kawase to solve once and for all the various problems surrounding the various versions of the Shohei printings of the Analects. Thus the significance of their donation to the Institute is all the greater.

I would finally like to comment briefly also about another of the works donated, the Yilijing zhuan tongjie. On the cover four characters are written in black ink, “Zhong yong zhang gou”. These are no more than a phrase that happens to correspond to the Zhongyong (the Doctrine of the Mean) that appears in the seventeenth volume. This work was one of thirty Song and Yuan works donated by Ichihashi Nagaaki to the Bakufu Academy and it contains an inscription (shikigo) by Ichihashi as well as the ownership stamp of the Academy. Since the inscription was penned by Ichino Meian, who had prepared the new edition (honkokubon) of the Shohei Analects, this work too is closely associated with the latter collection. The other twenty-nine precious works donated by Ichihashi are, as we have seen, now in the National Archives and other libraries. The Institute library owns the complete Song edition of the Yilijing zhuan tongjie; a comparison of the volume from the Yasuda collection shows that though they were not part of the same edition, they were one in line length and general style. The donation of the present volume is also significant in view of the historical ties that connect the old Bakufu Academy and the present university of Tokyo.

The Institute of Oriental Culture is a public facility which has a large number of works in its collection important for the study of printing and publishing, and as such strives to preserve these valuable works while at the same time allowing scholars to study them. The works donated from the Yasuda collection have thus found a fine home. It would have been Zenjiro Yasuda’s wish that they will continue to benefit scholarship, to the extent that the anomaly between the needs of preservation and the hands-on needs of the scholar can be solved.

former Associate Professor, Institute of Oriental Culture